Interest rates are really low right now–which is one of the reasons I lost my job at the beginning of the year. But my loss may also be my gain. Mortgage rates are also pretty low right now. I have about 24 years left on a 30 year mortgage, and the fact that I’ll be 74 when that’s paid off doesn’t sit well. Yes, I have other plans to deal with that, but I wouldn’t mind also doing something now. So I set out to find out if rates are low enough that I might actually benefit.

First of all I tried one of those internet loan sites. I didn’t get far before I quit. RocketMortgage wanted every bit of information needed to apply for a loan before I could even find out what terms I could get. I refuse to give out that much information until I know they’re really going to need it. Bye-bye, RocketMortgage. I went back to the brick-n-mortar reliables. Kinda.

My current mortgage servicing company has been after me for a while now to see about refinancing (and adding on a home equity loan if they could talk me into it), so I decided to hear what they had to say. I wasn’t impressed. They could do a 20-year loan that would cost me about $300 more a month.

Then I called the local broker I went with the two previous times. He actually had access to a 20-year loan for a lower rate than most 15-years. The net increase would be about $17 a month. Now THAT could be doable. But…should I? Was I forgetting something? After all, there would be fees, which they would try to get me to build into the loan. Would it be worth it to cut only six years off my loan? Time to crunch the numbers!

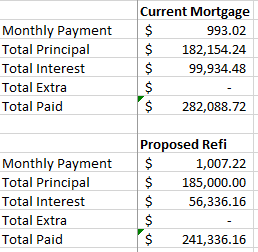

Armed with my current rate, number of payments left, and my current principal and interest payments, was able to calculate the total interest over the remaining life of the loan. That came to just under $100,000. I then calculated the total interest I’d pay on the proposed 20-year loan (figuring in financing the refi-fees, which I likely won’t do). That came to just over $56,000. Not a trivial difference! But I’ve heard that it can sometimes work to your advantage to pay extra principal on your loan to get it paid off sooner. I decided to look into that, even though at this point I’m not sure I would really want to take that money from other projects to do so.

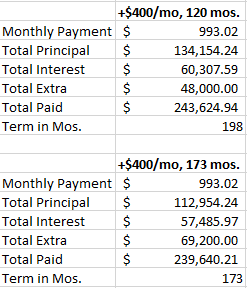

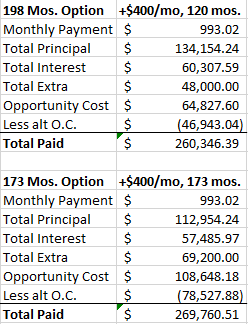

I played with several different models. I first tried applying $100 per month toward principal and discarded that option. It barely moved the needle. Increasing the pay-down, I found that if I paid an extra $400 a month toward principal for first 120 months I could get the total outlay on my current loan down to about $23000 more than I’d pay with the 20-year, and pay it off 42 months earlier–in just over 16 years instead of 20. And if I paid $400 a month for 173 months I’d have it paid off entirely–in around 14 years. That would be right before I hit retirement age–good timing!

But wait. Assuming that’s even $400 I have, I’ve also had people tell me it would be better to put that money into an investment that earns higher interest instead, have it build up faster, and use that to pay the mortgage off early. In any case, in my MBA program they taught us that when looking at any project you should compare what they called the “opportunity cost,” or what you might lose with this option over some other bench-mark option, such as a long-term fixed-return investment. You might do well with this option, but what if you did something else with it instead?

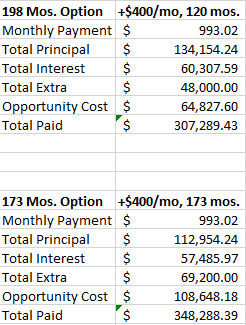

My financial advisor usually tosses around 6% as a fairly safe rate of return on long-term investment-i.e. bond funds with little to no risk, so I used that to calculate how much I would have if I invested the same $400 a month for the same length of time. In the 198-month scenario, where I put in $400 a month for 120 months I would have $64,827. In the 173-month scenario, investing $400 a month for 173 months, I’d have $108,648. Compared to my proposed refinance, by paying down my mortgage I’d be losing the additional principle I paid, but also losing the gains I might have realized by investing it. It’s something of a double-whammy.

But wait again. In both those scenarios I would be done making mortgage payments earlier than if I went with the 240-month refinance. Being done sooner would mean I could turn that $1007 monthly payment toward investments. What about the opportunity cost of that money? More quick calculations, and under the 198-month scenario, investing my monthly payments for those 42 fewer months, it would come to $46,943, and in the 173-month scenario, investing for 67 months, it would be $78,527. If we put that back into the picture we end up with a significantly smaller gap from the $241,336 total paid out on the 240-month refinance; about $19,000 to $28,000.

Of course these two scenarios really do depend on the availability of the $400 a month to apply toward principle. The opportunity cost is real, as the only prospect for finding that money would be to take from what I’m currently saving each month to invest. The savings in interest doesn’t keep up with the amount put in to pay down the principle, let alone with the interest earned on investing it.

Bottom line: My 20-year refinance would save me about $40,000 over paying out the rest of my 30-year mortgage, and about $19,000 to $28,000 over money-to-principle scenarios. The value of investing that proposed extra principal payment early on (i.e. over a longer period) is hard to beat, even versus a shorter term but larger amount later. Slow and steady wins the race, but more money up front gets you there even faster.

While the over-all benefits aren’t as high as I had hoped, in this case, the value of refinancing is pretty clear. I save four years and about $40,000, plus I get to take that proposed added principal payment (I still don’t now if I could swing that), and invest it at at least twice the rate of what I pay on my loan. I’d have to say it’s worth it to refinance.

Of course I’m no financial adviser, I haven’t given you all my details here, and I don’t know your circumstances. This isn’t really meant to tell you whether or not you might benefit. This is primarily an exercise to help you evaluate for yourself. Just remember to look at all angles, not just the most immediate. I probably missed something here, too, but I’m going into this much more sure of what I’m doing than if I had simply thought, “Four fewer years is always a good thing, right?”