I recently came across an address by Robert D. Hales that shared valuable insights into money and how we perceive it. I thought I’d share some of it here.

All of us are responsible to provide for ourselves and our families in both temporal and spiritual ways. To provide providently, we must practice the principles of provident living: joyfully living within our means, being content with what we have, avoiding excessive debt, and diligently saving and preparing for rainy-day emergencies.

…

How then do we avoid and overcome the patterns of debt and addiction to temporal, worldly things? May I share with you two lessons in provident living that can help each of us. These lessons, along with many other important lessons of my life, were taught to me by my wife and eternal companion. These lessons were learned at two different times in our marriage—both on occasions when I wanted to buy her a special gift.

The first lesson was learned when we were newly married and had very little money. I was in the air force, and we had missed Christmas together. I was on assignment overseas. When I got home, I saw a beautiful dress in a store window and suggested to my wife that if she liked it, we would buy it. Mary went into the dressing room of the store. After a moment the salesclerk came out, brushed by me, and returned the dress to its place in the store window. As we left the store, I asked, “What happened?” She replied, “It was a beautiful dress, but we can’t afford it!” Those words went straight to my heart. I have learned that the three most loving words are “I love you,” and the four most caring words for those we love are “We can’t afford it.”

The second lesson was learned several years later when we were more financially secure. Our wedding anniversary was approaching, and I wanted to buy Mary a fancy coat to show my love and appreciation for our many happy years together. When I asked what she thought of the coat I had in mind, she replied with words that again penetrated my heart and mind. “Where would I wear it?” she asked. (At the time she was a ward Relief Society president [ed. leader of the church’s women’s charity auxiliary] helping to minister to needy families.)

Then she taught me an unforgettable lesson. She looked me in the eyes and sweetly asked, “Are you buying this for me or for you?” In other words, she was asking, “Is the purpose of this gift to show your love for me or to show me that you are a good provider or to prove something to the world?” I pondered her question and realized I was thinking less about her and our family and more about me.

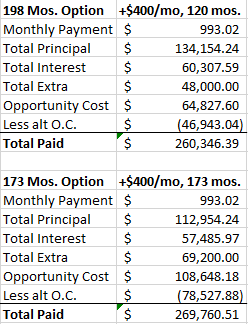

After that we had a serious, life-changing discussion about provident living, and both of us agreed that our money would be better spent in paying down our home mortgage and adding to our children’s education fund.

These two lessons are the essence of provident living. When faced with the choice to buy, consume, or engage in worldly things and activities, we all need to learn to say to one another, “We can’t afford it, even though we want it!” or “We can afford it, but we don’t need it—and we really don’t even want it!”

My wife has often been my backstop on financial issues, questioning the criticality of some of my desired purchases. I may not always have appreciated it at the time, but I do appreciate her keeping me grounded. I’m grateful for the partnership we’ve built through the years around managing our money. I do the bulk of the management and bill-paying, and she the bulk of the household shopping. This works well primarily because we share the same goals and we continually communicate.

Of course you don’t need a significant other to establish and maintain financial discipline. One of the key skills is to learn to distinguish between needs and wants, and when considering wants, understanding the root of that want. Developing the ability to police yourself and say, “I may not want this thing for the right reasons” is invaluable.

The bottom line with money is that either we learn to master it, or our money will become our master–or rather, those to whom we end up owing money. The more control we gain over our finances the greater freedom we will enjoy.