Sorry the posting has been light of late. There are reasons for that, and I’ll get to it some other time. But I stumbled across this today and had to share. Barricade Garage is becoming one of my favorite YouTube channels for the humorous yet pointed way they look at modern issues. I think we would all be better off if we could look inward and examine our own ways of thinking and our own flaws before we attempt to tell everyone how to fix their own. That is true self-reliance.

Category Archives: Intellectual

Securing your base

By now you all know I rather enjoy the site Art of Manliness, though frankly it could almost as easily be called the Art of Common Sense. There are certainly a lot of articles exploring “manliness” from all angles, but there is also a lot about basic preparedness and self-reliance.Take their recent article, Sunday Fireside: Secure Your Base.

Deriving supposedly from Carl Von Clausewitz’ “On War,” writers Brett and Kate McKay discuss what “securing your base” means in practical, civilian ways:

Securing your base means establishing a self-sustaining, shock-resistant “headquarters” that is well-defended against disruptions from external forces.

They list foundational concepts such as:

- Good health

- Financial independence (avoiding debt)

- Mechanical skills

- Domestic skills

- Strong social relationships with family and friends

- Firmness in beliefs

That last point I found most interesting, as it was the least predictable:

Finally, a secure base requires secure beliefs. While philosophic and political positions can and should evolve over time, they should not be so unexamined, so lacking in well-studied context, that every current of change knocks you into an incapacitating stupor of confusion and cognitive dissonance. You should know why you believe what you believe.

I suspect many of us are experiencing some of that confusion and cognitive dissonance these days amid the political and social turmoil in the United States and around the world. We are being simultaneously told that “Speech is violence,” and “Violence is speech” as valid, peaceful protests transform into destructive mobs inflicting significant property damage, cultural vandalism, and loss of life on the very people they claim to be supporting in their “protests.” The only way out of this mess as a society comes from people firm in their principles insisting on a better way forward than what we’re currently getting.

The purpose behind securing your base is best summarized by the authors, and I’ll close with this:

The purpose of creating this kind of personal garrison isn’t to passively retreat from the theater of life; rather, it is to create a fortification from which to better launch your offensive operations.

Your money or your life? It’s not that simple

About a month ago I began discussing an article from Wikihow.com on “4 Ways to Be Self Reliant,” by Trudi Griffin, LPC, MS. The article is more about relationships than what I would consider self-reliance, but she still makes some valid points. Today I want to look at her second point, managing money independently. She breaks money management down into six areas:

- Learn how to manage money

- Get out of debt

- Pay cash instead of using your credit card

- Keep cash on hand at all times

- Own a home

- Live within your means

To begin with Griffin warns against allowing others to manage your money. I agree with her basic premise, that you can lose your independence if you lost control of your money, but that depends on the nature of your relationship with that person. In most marriages one of the two usually assumes responsibility for managing the money. If you are good at communicating, have compatible financial goals, and trust one another it’s actually easier to have one partner take primary responsibility and keep the other informed. Her second concern is more valid: if the primary money manager is unable to continue in that role it may be very difficult for the other partner to step in. Even if you are not the money manager in your relationship, make sure you know how to access everything and are comfortable managing money yourself.

Griffin also encourages everyone to get out of debt, though what she really focuses on is keeping your debt manageable. According to her, your total long-term debt payments (mortgage, auto and school loans, and credit card debt) shouldn’t exceed 36% of your monthly income. If your debt payments exceed this level you should make every effort to get that debt load paid down as quickly as possible.

As a corollary to that, Griffin also advocates paying cash for everything, and to keep cash on hand (and in savings) at all times. This seems primarily to be to keep your credit card debt low, and I somewhat agree with this. If you have difficulty paying off your credit cards, or can’t resist charging more money on them, then by all means you should avoid using those credit cards. But if you have developed financial discipline and never miss making your payments because you’re able to set money aside to make those payments, there may be a way to make your credit cards work for you.

I recently read I Will Teach You To Be Rich, by Ramit Sethi. The man has some good ideas about acquiring, building, and managing wealth–and some ideas I’m less keen on. But one suggestion he makes is to put your regular expenses, as much as possible, on your credit cards and then set that money aside to pay the bill off quickly. If you get the right credit card you can earn travel miles or cash back rewards that amount to free money. I’m disciplined with managing my budget, and so I decided to try it. I haven’t put as much on my card as I could, but already within the past several months I’ve picked up nearly $250 of cash back rewards. It’s free money. But if you’re not so good at managing your credit card debt and paying off your account monthly, it’s best to follow Griffin’s advice and avoid credit cards altogether.

Griffin’s next suggestion is to own a home. I’m not as sure about this one as I once was. Right now interest rates are low, so you may only pay about 50% more than the cost of your house in repaying the loan. Depending on how long you live there, the value of the home may increase well beyond that. Our first house did just that. But you don’t always control how long you live somewhere these days. We had to move when I lost my job ten years ago, and the timing was terrible–the housing market had collapsed and I owed considerably more on that house than I could sell it for.

There’s also the maintenance costs and hassle of a house to consider. So far since moving into our house nine years ago we’ve replaced the roof, replaced the furnace, air conditioner, and water heater, and bought high-efficiency windows. Granted, that last purchase was voluntary, but that was easily an additional 30-40% the cost of the house we had to find within the first six years of buying it. That, on top of a myriad of other maintenance expenses through the years. If you don’t like or can’t afford doing your own maintenance, or if you can’t be sure how long you’ll be staying where you live, a house may not be the best option. Everyone needs to evaluate their priorities themselves in this area.

Last, but by no means least, we should live within our means. That usually means several things that have to happen. First, you need to know (or learn) exactly how much money you spend each month and where it goes. Second, where at all possible, and perhaps not matter what the sacrifice, you need to adjust your spending to where it is less than what you earn. Third, you need to continually monitor your spending and your justifications for spending and see how you measure up against your budget. You need to be willing and able to adjust your spending to remain below your means–and save the difference religiously.

Frankly, learning how to budget and how to stick to that budget is one of the most important skills one can develop for self-reliance. That’s pretty much the key to achieving financial independence and taking care of “future you.” Or perhaps your spouse and children after you’re gone. Usually in life there are only two choices: either your master your money or your money masters you. Money is seldom a kind master, but it can be a real friend when you learn to master it. Mastering your finances is a key step toward true self-reliance.

Free thinking – not really free

The problem with being a free thinker is that it just takes so much more time and effort than just accepting whatever your told. Now, of course I’m saying this tongue-in-cheek, as the cost of not questioning much of what you hear is potentially much, much higher. But in an era when information is available at much higher volumes and speed than any of us can hope to consume, it’s a considerable sacrifice to weigh everything critically.

Take for example the reporting on a recent Gallup poll. I first learned of this poll via an article on a news and opinion site that trends conservative. The headline read thusly:

Gallup Poll Shows That No One Thinks the Media Is Doing a Good Job During the Pandemic

Rick Moran – PJMedia.com

The article cites another article from the Washington Examiner also reporting on the same Gallup Poll, so I went to read the Examiner article. Their headline?

Media botched the virus crisis and made it ‘worse’: Poll

Paul Bedard – WashingtonExaminer.com

And then I got a novel idea: Let’s go look at the poll itself! There were links, so…why not? Note we are now heading three layers deep. And how do they title the results of their poll?

Public Sees Harm in Exaggerating, Downplaying COVID-19 Threat

Jeffrey M. Jones and Zacc Ritter – Gallup.com

Following this trail of headlines just by themselves we see the effect of ye olde “Telephone Game.” We somehow went from “over- or under-playing the threat both believed to cause harm” to “The media is doing a poor job.”

But wait, we still haven’t even looked at the actual text of the articles yet. I’m going to ignore the first two and focus in on just the article written around the presentation of the data itself. Here’s their lede:

Media bias is a great concern for Americans, and the implications of such bias for society are magnified when the nation is in crisis, such as the current coronavirus pandemic. A new Gallup/Knight Foundation survey finds that a majority of Americans are concerned about biased news coverage of the coronavirus situation, including reporting that downplays the threat but also reporting that exaggerates it.

Democrats and Republicans diverge on whether exaggerating or downplaying the coronavirus threat is the greater risk. However, they generally agree that the crisis is worse than it needed to be, and that the news media should not wait for the crisis to ease before reporting on official actions that exacerbated the coronavirus situation.

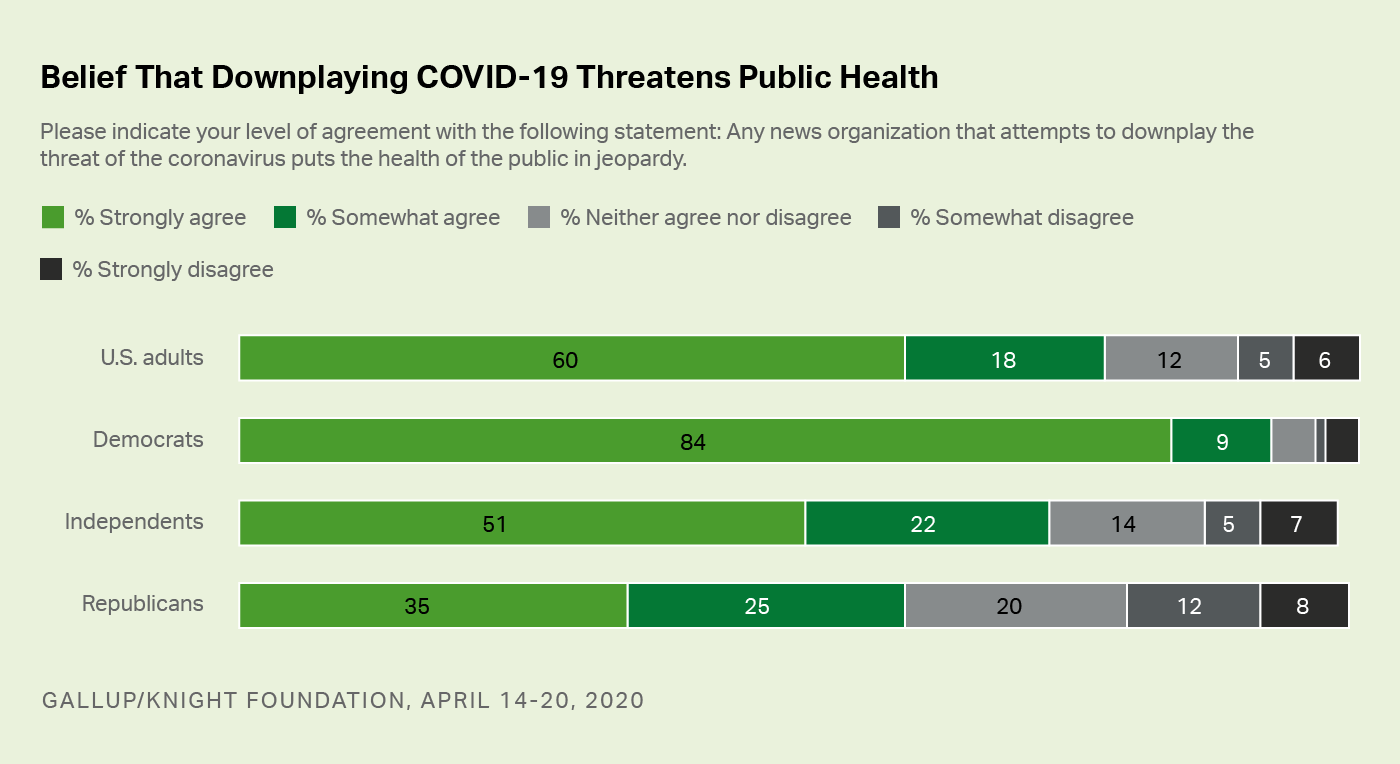

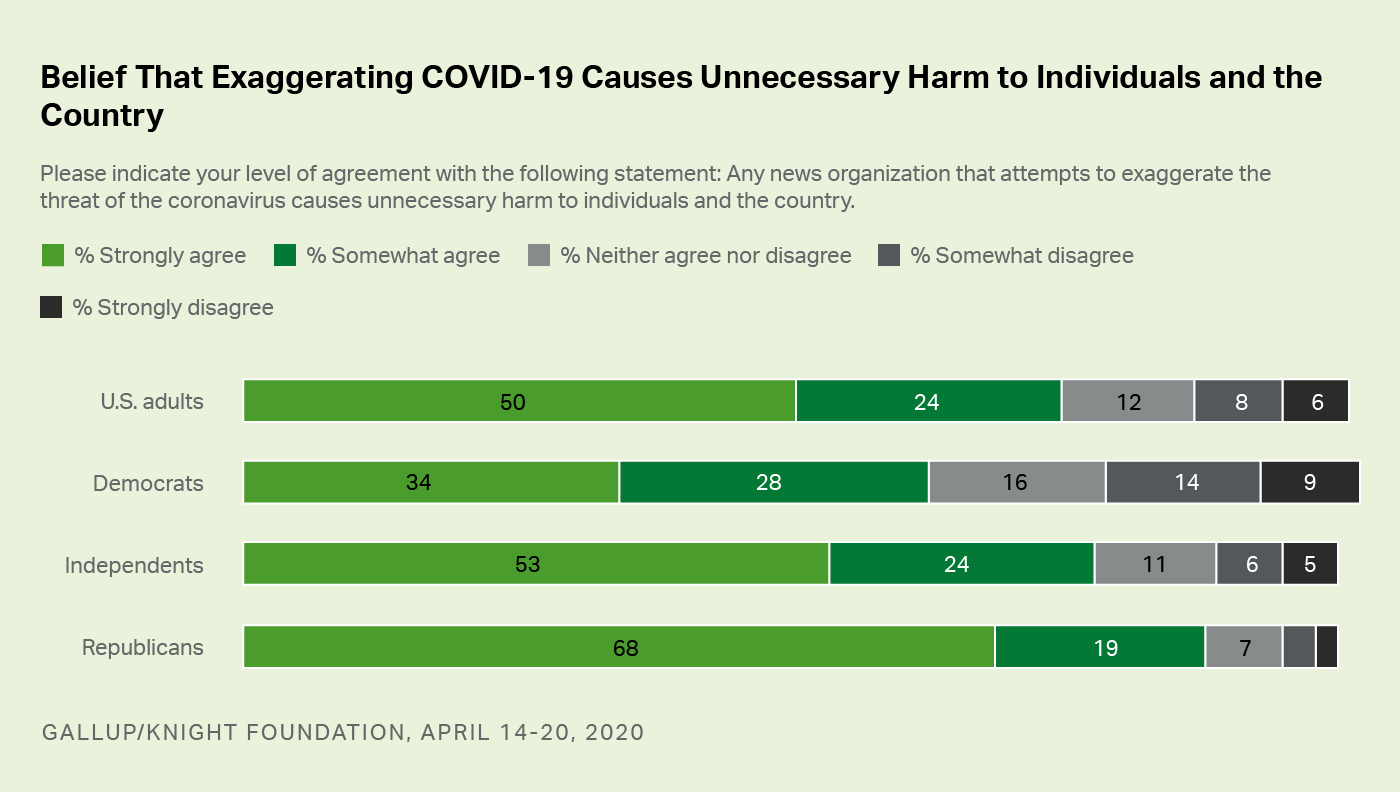

It seems like a pretty good summary. Let’s look at the questions asked and the data obtained and tabulated:

This is as far as the first two articles really get. They focus in on the Republicans vs. Democrats angle, and also on the fact that the majority of all Americans find both exaggeration and down-playing to be harmful. But outside of the data itself, notice something a bit off? They’re asking what they essentially treat as inverse questions, but they word them slightly differently each time. When asking about down-playing they ask if it threatens public health. When they ask about exaggeration, they ask if it causes unnecessary harm to individuals and the country.

Why would they ask them differently? Wouldn’t it make the most sense to ask either “Any news organization that attempts to [down-play/exaggerate] the threat of the Coronavirus causes puts the health of the public in jeopardy” or “Any news organization that attempts to [down-play/exaggerate] the threat of the Coronavirus causes causes unnecessary harm to individuals and the country”? Wouldn’t that make the two questions equally weighted and inverse?

This may be displaying some of my own bias here, but it seems to me that framing the harm in terms of “public health” would tend to grab the interest of Democrats, while framing it in terms of individuals and the country would resonate more with Republicans. I don’t think it’s a coincidence that those groups do tend to rate the harm higher accordingly. Independents, predictably, seem to walk the middle of the road. Could it be this poll was designed to elicit a desired result outside of the stated objective?

But let’s look at the remaining questions and results:

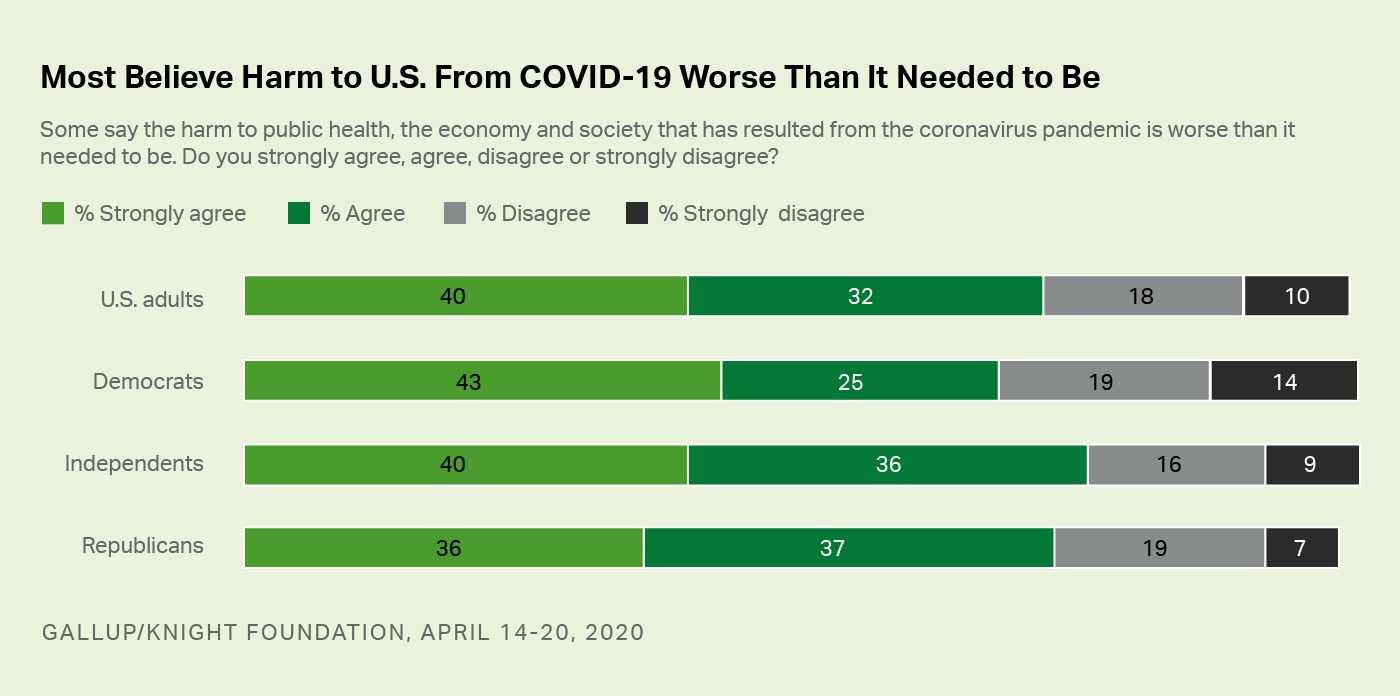

The third question is fairly straightforward: Was the pandemic more harmful to the US than it needed to be? Interestingly here the independents agree most, but pretty much everyone agrees that it was. But what I don’t see here is any particular assignation of blame. We also don’t see any attempt to define “harm.” Was the harm in terms of public health, or to individuals and the country? Do people believe the unnecessary harm was caused by media reporting, let alone exaggeration or down-playing? That’s not part of the question. What about a lack of solid information, down-played or exaggerated? Also not addressed. One might infer the Democrats think the harm came from downplaying, while Republicans think it was from exaggeration, but causation was never addressed in this question. People simply think more harm was done than should have been.

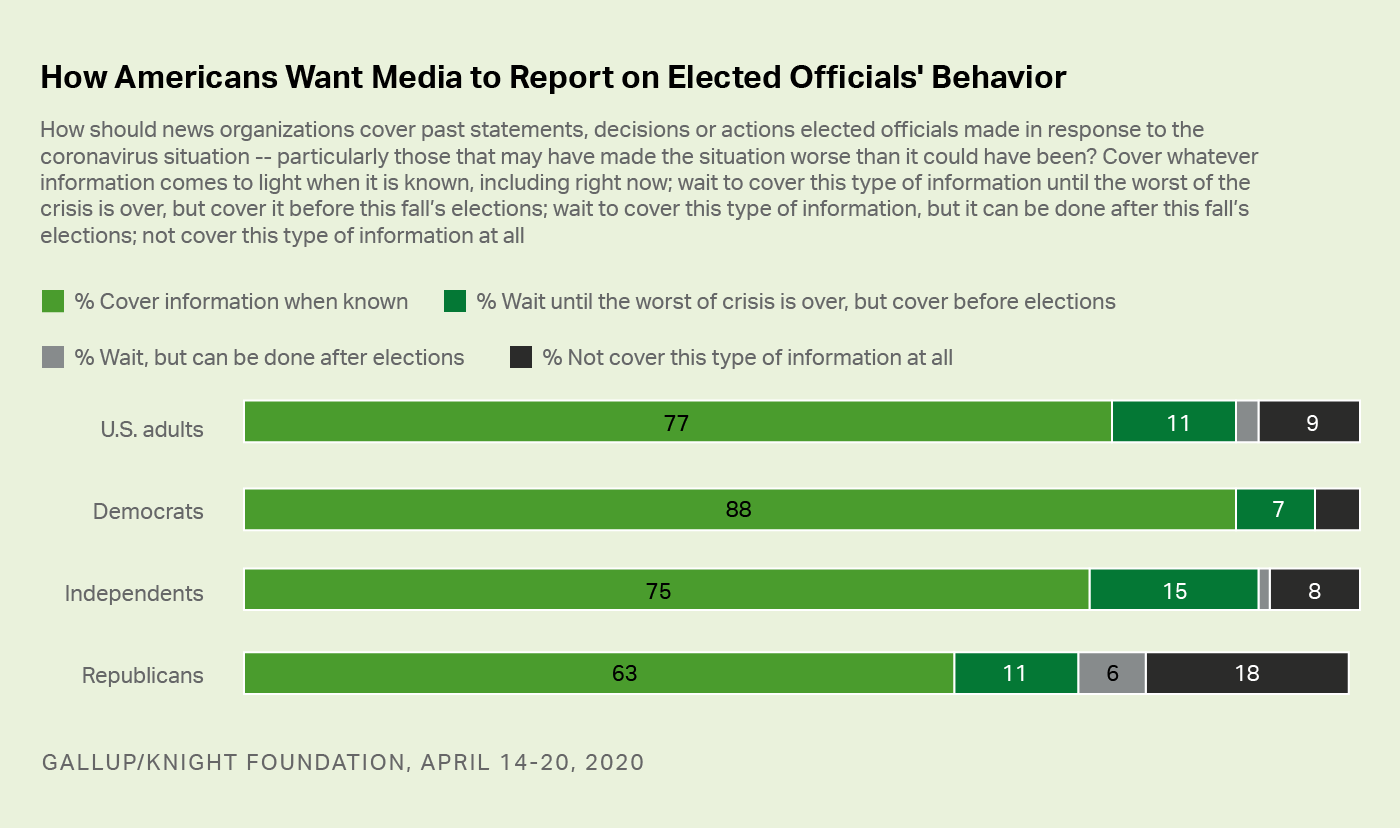

The last question is just kinda of weird. It asks how people want the actions of public officials and the effects of their decisions to be reported on. Not surprisingly, as Donald Trump seems to be the main central figure under the microscope much of the time, a very high number of Democrats want them covered now. But also a high number of Republicans want coverage now, as well. But really, what value do we derive from this question? Evidently pretty much everyone wants the media to cover the actions of public officials and the results of those actions. There’s nothing at all here about whether or not we trust the media to cover it fairly, or even if we want it covered fairly. There’s really nothing here to support the Washington Examiner’s supposition that we believe the media botched their coverage. Same for PJ Media’s claim that the poll shows the media is not performing well in the crisis.

Okay, thanks for sticking with me this far. The bottom line here is regardless of what I think of the validity of the poll, the pollsters themselves did not attempt to read anything into the data that wasn’t supported by the data. They did a decent job. Less admirable was the news media’s interpretation thereof. Both headlines and articles try to get more out of the data than is really there. I’m not entirely sure about the Examiner’s leanings, but a quick online search suggests they lean right. And the right tends to be convinced that the media is biased left and/or doing a poor job of unbiased reporting. While it’s amusing that we have media claiming the media is doing a poor job, it seems evident they’re claiming it with very little substance to go on here.

But if we weren’t aware of their bias beforehand it would be easy to assume that the PJ Media article’s assessment is correct because it echoes the Washington Examiner’s assessment. And since PJ Media quotes from the the Examiner, they invite us to not look any further, not even to read the Examiner’s article. We have to dig down two levels to find that both media outlets are creating something out of nothing.

As much as I hate to say it, because I’m basically a lazy man, to be a true free thinker we have to do our homework. To do otherwise is to be misled. And the world needs more true free thinkers.

Is it worth it?

Ken Jorgustin at Modern Survival Blog takes up the question of whether it’s worth it to invest in self-reliance. He looks at various types of home production, such as raising your own chickens, growing your own garden, or even switching to solar energy all cost money, and often those same products can be obtained commercially for less.

During the process of building their palace, I’ve thought about the money it took to get this done. As well as the ongoing costs of maintaining the small flock, and feeding them. Let me put it this way. You might get depressed to realize the ultimate cost per dozen eggs output compared to the money input!

Ken Jorgustin

I’ve noticed that with gardening. In both places we’ve lived our irrigation and gardening water comes from the same water as our culinary and hygienic water, and the cost can more than double during the summer months. Whatever money we save by growing our own vegetables is more than eaten up in the water, seeds, tools, and fertilizer needed to grow them. We ultimately decided it simply wasn’t worthwhile to try to grow our own potatoes in Idaho.

We also looked at solar power ourselves a few years ago and realized that in spite of what the salesman told us, the system would never pay for itself, even if the power company paid for any excess electricity we generated–which they stopped doing within a few years. While we would like to have been able to do more to reduce pollution and our own energy dependence we just couldn’t justify the expense.

It can all be enough to make you step back and wonder if it’s really worthwhile to take a different path. But, as Jorgustin explains, the answer will be different for everyone. For some people cost is the only consideration, and they’ll likely not bother with many self-reliance measures. For my wife and I, we find home-grown food is usually healthier and better tasting. What’s more, there may be rough times ahead–times when the stores won’t be able to get the stock they usually get. We may very well need to supplement our food supply from our own yard. In the middle of the crisis is not the time to be learning what grows and what doesn’t, or how to lay out your garden, your watering, etc. And as we’ve seen, the price of things can increase quickly when it’s in short supply.

A considerable part of self-reliance, and especially emergency preparedness, is not just having the things you need when things go wrong, but knowing what to do with them. Maybe not everything we can do we should do, but it is worthwhile to consider what things you want to be able to do. And sometimes it just feels good to do it.

It’s the little things that count

I always get a little excited when I see the concept of self-reliance brought up in unexpected places or referring to aspects outside the usual “prepper” mindset. After all, my philosophy of self-reliance is much broader, and should be more applicable to everyday life by everyday people. So it caught my attention when I found “7 Tips for Increasing Self-Reliance” on The Law of Attraction.com.

Some of their seven points are somewhat familiar, such as “Accept Responsibility” and “Make Your Own Decisions,” but others are are a little less obvious–or at least less practiced these days.

Take Point #3: Learn More Practical Skills:

The more practical skills you have in your toolkit, the fewer chances there will be for you to feel helpless or need other people to come to your rescue. While you should feel free to call out experts to help you with complicated household problems and mechanical difficulties, it’s great if you can at least do the basics for yourself. Get some books or join some classes.

Try to get a better grasp of everything from plumbing to IT, electronics and cooking.

A few (dozen) years ago I spent two years in Australia as a missionary for my church. Before we travel to our assigned locations we spend anywhere from three to eight weeks learning teaching skills and, where necessary, a new language. From the beginning we are paired up with another missionary, who we will be with 24/7.

My companion was a really pleasant fellow from solid farm stock (Central Utah turkey farmers), but I was soon quite surprised to find he had no idea how to do his own laundry! Nor did he know what to do when he spilled dinner on his tie. Now, I won’t claim to have been anything but a burden on my mother up until that point in time, but she had at least taught me how to do laundry, how to cook, how to sew on buttons and mend pants. I gladly dispensed my wisdom to my companion, and I have definitive proof he was able to survive the entire two years.

A few years later while I was in college I went to an activity with a bunch of other college students. We decided to go get some ice cream or something afterward at a place several blocks away. While I was driving through campus I realized my tire had gone flat. I pulled over into a parking lot and started pulling out my equipment to change it for my spare.

Before long about a handful of young women from our group had pulled over to see if everything was okay. When I explained what the problem was and that I’d be okay, they all insisted on staying to watch. No one had taught them how to change a tire! I was only too happy to demonstrate for them, of course.

Whether it’s hanging a picture, or strengthening a wobbly chair, or reattaching things that come loose, there are a lot of simple tasks in life we can easily take for granted and forget to either learn or pass on. There’s no reason we should be helpless when it comes to using basic tools to perform simple maintenance tasks. Fixing a leaky faucet–or outright replacing one–isn’t difficult, but if you have no idea how to go about it you might be tempted to spend a decent chunk of money on something that shouldn’t take very long.

Learning some basic skills will pay off in spades sooner or later. And it might just help you get the girls! (Okay, not really. They were all impressed, but that’s about as far as it went.)

Who do we trust our lives to?

I had a brief discussion with a friend on Facebook the other day in which it became apparent we have differing opinions on the role of government. I don’t think either of us will change the other’s mind any time soon, but he said something that stuck with me. It was essentially, “We trust the government with our lives, so why not to distribute wealth?”

I had to stop and think about that. Do we trust the government with our lives? Should we?

Ultimately I suppose we do trust the government with our lives to some extent. I rely on my local city government to provide me safe drinking water–something they failed at not so long ago. I’ve since taken steps to lessen that risk, but truth be told, if there’s something dangerously wrong with my water I may not know it in time unless the government warns me. I have to trust that they’re doing their best.

I also trust the national government to maintain an army sufficient to deter any other country from coming in and killing me. As we’ve seen in recent years they’re not entirely successful in that responsibility, but they’re keeping the risk acceptably low. And they’re also doing a decent job at deterring those who might take shortcuts or act irresponsibly with our food supply. Incidents still happen, but still, the risk is still quite low.

There are, however, many more ways in which to die. In most of those cases the government acts more as a deterrent than a protection. They can’t keep some idiot driver from cutting across four lanes of traffic to make their exit and plowing into me instead. They can’t guarantee my neighbor’s tree isn’t going to fall on my house as I sleep and crush me. They can’t guarantee the airplane I get on isn’t going to crash, nor can they promise me I won’t die during heart surgery at some future point.

All they can do (or perhaps more accurately, are willing to do at present) is tell people what they should or shouldn’t do, and then affix punishments for noncompliance. And for the most part that is enough. Most people don’t act irresponsibly or seek to do deliberate harm, and they wouldn’t, even without those laws. And many more also don’t because they find the potential punishment sufficiently unpleasant.

And yet 90 people per day are killed in car accidents in America. Several million every year are injured, many permanently. Is the government failing or succeeding? If their responsibility is to protect our lives, I’d say they’re failing. We’ve lost over 80,000 Americans to the Coronavirus this year in spite of all the protections government can provide, including some fairly dramatic precautions. At the same time, those measures have cost lives as well, to say nothing of the jobs at least temporarily lost. The long-term impact on lives may not be fully understood for years yet.

So I guess one question to ask ourselves is whether or not any government can guarantee us our lives. Can a government eliminate all risk? And would we like it if they did? What would our lives be like? I see plenty of examples all around right now of people starting to push back against government control over their lives as the governmental restrictions put in place to save lives from COVID-19 continue in effect well into the second or third months. I live in a state that imposed less strict restrictions and perhaps coincidentally, perhaps in correlation with other factors, has the fourth lowest death rate in the country. I’ve pretty much willingly complied with those restrictions.

But when I hear of some of the other states’ more extensive efforts to control the virus by controlling people I am particularly grateful to live where I live. I fully understand why those states are facing popular backlash. Clearly, even if a government could keep us all from dying, most people feel those all-controlling restrictions would make life no longer worth living, especially when there is no end in sight.

In fact, history seems to prove that a restrictive government, even in the name of protecting life, tends to fall sooner or later. Human nature tends to lead governments to go too far, and usually for decreasingly benign reasons. They may start out well-meaning, but soon grab more and more power simply for the sake of hanging onto that power.

But then let’s look at the alternative. A total lack of government tends not to work very well, either. While I don’t entirely subscribe to the “Lord of the Flies” theory of humanity, a complete lack of common law–or the enforcement thereof–tends toward disaster. People will usually work out some sort of pact, a set of rules for maintaining peace, property, and ensuring basic rights. But as demonstrated by certain parts of our current world, the rule of “might makes right” is more common than we’d like to think.

Humanity needs government. It’s even part of my religion’s basic tenets. Governments that ensure basic rights and basic rules governing human interaction are essential to maximize productivity, cooperation, and peace. But in all cases it falls upon the governed to govern themselves to some degree. The value of traffic laws to a victim is not in the enforcement of those laws, but in the threat of enforcement. It does me precious little good if I’m dead knowing the idiot that decided to continue through the red light at 50 miles an hour to broadside my car will be heavily fined and potentially jailed. The hope is that, knowing he could be heavily fined and jailed, the person will choose not to speed and run red lights in the first place.

And yet we still lose around 40,000 Americans to car accidents every year. If we apply the same logic to cars I’ve been hearing about the coronavirus, we should all be voluntarily getting rid of our cars or agreeing to cap our speed at ten miles an hour. We’re not, and we won’t. Deep down even the strongest proponents of government protection in all area of life seem to accept that communal rights must be tempered by individual rights. We’re willing to accept responsibility for protecting ourselves in order to avoid our own inconvenience.

In fact, as a society in America, we still retain far more personal responsibility for our own protection, prosperity, and happiness than we surrender to government. There is constant pressure from some to push more and more of that control to government, but much of it seems to be due to some mistaken belief that such power could never be abused, or that the other party who we distrust/hate so dearly will never actually hold power, giving them the opportunity to abuse the power we want to hand the government when under our side’s control.

That’s why I tend to believe that we need to be self-reliant rather than government-reliant, especially when it comes to protection. The deterrent power of government is important, but they can’t (and probably shouldn’t) be everywhere. As the saying goes, when seconds count, the police are only minutes away. Ultimately we can’t completely avoid all danger in life. But we can take responsibility for our own safety.

Hopefully every one of us who has taken formal drivers education has been taught to be aware of what’s going on around us in order to anticipate threats. Hopefully none of us, seeing that idiot in the far left lane who suddenly realizes they should be in the far right lane, just continues on at the same speed, staring straight ahead, trusting entirely in the law to protect us. We slow down. We start looking for room for evasive action. We do our best to make sure we are not in their path.

Most anyone who is looking after their financial future recognizes the inadequacy in America of the government safety net to support the retired. Even assuming Social Security will survive all the political wrangling around it, most retirement plans include coming up with funds well above and beyond what we can count on from the government. Similarly, during the two years I spent on unemployment, had I needed to rely on that alone my family would have really struggled.

We can’t anticipate everything, but we can take reasonable precautions in much of what we do. We can take steps to reduce negative impacts on those we love. We can act morally and responsibly in our interactions with others. We can think before we act.

I think, whether we like it or not, so long as we choose to live within society, within the bounds of modern infrastructure we’re going to have to trust government at some essential level. If we don’t trust in our social structures to at least some degree we will spend the majority of our time and resources trying to eliminate any and all dependence on government and other people, effectively pushing us to the lowest level of Maslow’s Hierarchy, and that’s not where we should be. We need to be able to trust that a vast majority of the time when we turn on our faucet, when we flip the light switch, when we set out to drive to work we’re going to have a predictable, quality experience.

At the same time, where the absence of that predictable result threatens our lives, we need to be prepared to shoulder that burden ourselves, if only for a short time. I’ll drink tap water, but I’ll make sure I’ve got a reserve supply in case I can no longer trust that water. I’ll enjoy all the daily benefits of electricity, but have other options available in case it fails. I’ll do my best to assume every moment I’m in my car that other drivers may not abide by the law. Government is very good and beneficial for many things. But over-dependence on them can be deadly. Our own safety and happiness must always be our responsibility.

Work is essential

Mike Rowe has become something of a hero of mine. The man observes, thinks deeply, and explains himself very well. People try to impose a political agenda on him, but by and large his thoughts don’t lay with any particular ideology.

Recently he was interviewed by Dave Rubin, but don’t let that worry you. Their discussion transcends politics, at least in my view, and explores what I would consider the bedrock of humanity and a major pillar of self-reliance: the value of work.

I agree with Mike. It’s dangerous to our long-term survival as a country and culture, and perhaps even as human beings, to place too high a value on education and too low a value on work. I say this as a person who has an MBA and works a white-collar technology job. I can’t say I’m enamored with physical labor. But I’m not afraid of it. I’ve built a shed from scratch at each of the three houses I’ve owned. I’m used to doing most of the physical labor required for maintaining my property, be it fixing sprinklers, landscaping, laying flooring, or basic plumbing. And I do find shoveling snow to be oddly therapeutic. I only hire others when I need it done quickly, am concerned for my safety, or the skill-set is not something I can acquire quickly (or can afford to do wrong).

And I’ll tell you what, I’ve felt as much satisfaction from the physical things I’ve accomplished as from the “knowledge-worker” jobs from which I support my family. I’ve been involved in projects that save companies millions of dollars. I’ve saved people’s jobs with my recommendations. I’ve uncovered the causes some of the most daunting system errors. I get as much long-term pleasure from a bookshelf I’ve built.

That’s not to say I get no satisfaction from my education. I’ve also been a partner in building up a successful brick-n-mortar business using the tools I acquired in my MBA program, and that little venture has been one of the high points of my life. But this idea of education being the be-all, end-all of existence is ridiculous. My first degree was in Music. I enjoyed every minute of it. But ultimately that degree left me unemployed in Pocatello, Idaho (possibly worse than Greeeeenlaaaaand) and depressed out of my skull. And what got me out of it and into my career wasn’t my education, but my ability to learn. The two are not synonymous.

But whatever we do, I would certainly hope we derive more from it than a paycheck. There ought to be some satisfaction from the work itself. I would hope those who serve me in some capacity derive pleasure and satisfaction from their work. Sooner or later I’m going to need heart surgery, and I would feel much better knowing my surgeon is passionate about heart surgery, and not just viewing it all as just another transaction. I’d want him actively concerned about whether I live or die, and not just whether I’ll be able to pay him or not.

I’m not entirely sure where I’m going with this, except perhaps for this: it is foolish to denigrate physical labor, perhaps even dangerous. The point of our lives should not be avoiding work, or working only so we can play, or even working only so we can retire. Most of us will spend the majority of our adult lives working in some way. Hopefully we can derive a little satisfaction, a little pride in our work, along the way. And hopefully our society will learn to value that work, regardless of what it is.

Is college headed online?

Scott Galloway, a Silicon Valley prognosticator with a respectable track record is predicting the Cornavirus and resulting stop-gap measures of moving education online is going to become the disruption that changes the university system forever, with tech companies partnering with colleges to become hybrid, virtual campuses. In an interview with James D. Walsh of New York Magazine he had this to say:

Colleges and universities are scrambling to figure out what to do next year if students can’t come back to campus. Half the schools have pushed back their May 1 deadlines for accepting seats. What do you expect to happen over the next month?

There’s a recognition that education — the value, the price, the product — has fundamentally shifted. The value of education has been substantially degraded. There’s the education certification and then there’s the experience part of college. The experience part of it is down to zero, and the education part has been dramatically reduced. You get a degree that, over time, will be reduced in value as we realize it’s not the same to be a graduate of a liberal-arts college if you never went to campus. You can see already how students and their parents are responding.

At universities, we’re having constant meetings, and we’ve all adopted this narrative of “This is unprecedented, and we’re in this together,” which is Latin for “We’re not lowering our prices, bitches.” Universities are still in a period of consensual hallucination with each saying, “We’re going to maintain these prices for what has become, overnight, a dramatically less compelling product offering.”

In fact, the coronavirus is forcing people to take a hard look at that $51,000 tuition they’re spending. Even wealthy people just can’t swallow the jagged pill of tuition if it doesn’t involve getting to send their kids away for four years. It’s like, “Wait, my kid’s going to be home most of the year? Staring at a computer screen?” There’s this horrific awakening being delivered via Zoom of just how substandard and overpriced education is at every level. I can’t tell you the number of people who have asked me, “Should my kid consider taking a gap year?”

…

Ultimately, universities are going to partner with companies to help them expand. I think that partnership will look something like MIT and Google partnering. Microsoft and Berkeley. Big-tech companies are about to enter education and health care in a big way, not because they want to but because they have to.

Let’s look at Apple. It does something like $250 billion a year in revenue. Apple has to convince its stockholders that its stock price will double in five years, otherwise its stockholders will go buy Salesforce or Zoom or some other stock. Apple doesn’t need to double revenue to double its stock price, but it needs to increase it by 60 or 80 percent. That means, in the next five years, Apple probably needs to increase its revenue base by $150 billion. To do this, you have to go big-game hunting. You can’t feed a city raising squirrels. Those big-tech companies have to turn their eyes to new prey, the list of which gets pretty short pretty fast if you look at how big these industries need to be in that weight class. Things like automobiles. They’ll be in the brains of automobiles, but they don’t want to be in the business of manufacturing automobiles because it’s a shitty, low-margin business. The rest of the list is government, defense, education, and health care. People ask if big tech wants to get into education and health care, and I say no, they have to get into education and health care. They have no choice.

There’s a certain amount of sense in what he’s telling us. American universities have begun to lose sight of their original purpose: to dispense knowledge. They’ve become factories for wholesale social change, and in the process have added so much overhead to their cost structures that the price of their knowledge-offering has increased exponentially while the actual value grows increasingly questionable. And now the Coronavirus has shown students that not only is the knowledge product not worth the cost, but the online experience has diminished it even further. It seems doubtful that universities will be able to continue charging $50,000+ a year for Zoom classes. Where they once derided online universities such as University of Phoenix (my MBA alma mater) they may find themselves studying their models, perhaps even purchasing them outright.

However, if such a model is to work there will first come a major upheaval. Today’s teachers are ill-prepared for the online classroom. I’ve been watching as my sons have struggled with on-line school from their local high school. The quality and intensity of the assignments have diminished, while the teachers largely have retreated to a consulting role, not even attempting to teach the subject matter in even a virtual classroom setting (with the interesting exception of their release-time religious studies teacher). One son is struggling mightily to complete the two classes most critical to his future career plans because the teacher had largely left them on their own.

I don’t doubt there are teachers who can adapt, improvise and overcome, and perhaps even thrive in this new model, especially at the college level. As I mentioned above, I earned my post-graduate degree in a hybrid setting, long before video conferencing software became cheap and ubiquitous, and we were able to make it work. But we were all working professionals who had outgrown the need for classroom learning. We knew how to learn. This model may not work so well for K-12 education, and I suspect it won’t be applied any time soon.

The university system, however, is ripe for it. The real question is whether universities will be willing to give up their role as engines of social change and retreat back to mere education. Or will the corporate partners assist them in policing the minds of their students more efficiently than ever before? We may be on the verge of a fundamental ground-shift, and only time will tell if it was for better or worse.

COVID Confusion

I found this in our local monthly/marketing newspaper in a humor piece of things the author learned from social media during the COVID-19 quarantine:

In effort not to get sick we should eat well, but we should not go out to get healthy fresh food when we run out and eat whatever pre-packaged food we have on hand instead. However, we should order out at our local restaurants to help keep them in business. Then it’s okay to go out to pick up the food. Your food might be prepared by someone sick that doesn’t know they are sick, but that’s okay if you pay by credit card and take the food out of the container. However, you should avoid going to the grocery store at all costs because you might get sick.

Joani Taylor, “The Social Media Scandal – What I Learned During Quarantine”, Sandy City Journal

If there is anyone left out there who still believes there’s a perfect response to a pandemic, especially one where the details about the virus aren’t really known…well, they’re probably on social media telling the rest of us what we should be doing. I’ve been fortunate enough to live in a state that took a somewhat moderate approach, while managing to keep the death rate fairly low, but the nags and scolds have been everywhere all the same.

Sure, I get it. People are scared, and fear makes people thrash about desperately in search of some way to feel in control. For many people that means lecturing everyone else. But the rest of us, when faced with conflicting information, reach a point where we just have to decide for ourselves which advice we can keep and what risks we are willing to take. Here are a few of the things I’ve learned (or re-learned) from all of this:

- Preparation buys time. We were not as prepared as we wish we’d been, but we still had at least several weeks worth of all essential items. Even though we weren’t sure how long our toilet paper supply would last, we had enough to hang in there until more started appearing. We didn’t need to panic, spend exorbitant amounts of money to secure the essentials, and could put off even shopping for groceries until things calmed down.

- People don’t want or can’t handle fresh. When we did go shopping we had no trouble finding fresh fruits and vegetables. Do people just not buy the more perishable items in an emergency? It’s not like we were without power. Veggies keep for weeks in the fridge. Or do people just not know how to prepare fruits and vegetables anymore? Not that I’m complaining. We’ve been able to eat healthy while everyone else, from the look of the store shelves, are existing on flour, pasta and beans.

- Savings are essential. I am one of the fortunate people who can work from home, even if it’s not my preferred way to work. But even I had been furloughed or laid off we would have had savings to get through this.

- Flexibility and resilience help. When things like this happen we can sit back and complain over every inconvenience or difficulty, or we can relax, take a deep breath (or two or three), and deal with everything one step at a time. This is easier to do if you’re not worried about basic survival.

- Cut everyone some slack, including yourself. I’ve had to continually remind myself that people are experiencing widely varying levels of stress right now. On the other hand, if there were people whose stress was causing me stress, I’m not obligated to keep absorbing their stress. There are some where I hit the “social media snooze button” so I wouldn’t have to deal with them until things calm down again. For the most part people have been keeping things on an even keel, and when they aren’t I would try to be kind and remember where they’re coming from.

- Even introverts need people. While introverts across the world have been cheering about this being the moment they were born for, the truth is, introversion does not mean we don’t need anyone else. Introversion/Extroversion is more a matter of where we get our energy from. Extroverts get their energy from being with others. Introverts get theirs from being somewhat isolated and quiet. We can enjoy social interactions, and even get some energy from particularly enjoyable ones, but most drain energy from us, and sooner or later we need to get away and recharge. Being shut up at home hasn’t been particularly difficult for me, but after a couple weeks I found myself reaching out to people much more than I usually do. I miss the depth, breadth and variety of my normal interactions.

- Focus on what you can do. This crisis quickly revealed where our family is not as prepared as we should be. The problem is that some of that just can’t–and perhaps shouldn’t–be fixed right now. We found we were least prepared in our supplies of paper products, baking supplies, and a few other food categories. And yet if we’ve learned anything about shortages, it’s that running out and stocking up just make things worse for everyone, so we’ve had to resist that urge. Instead, we identified some things we can procure right now, and we’ve focused on that. We have a much better water storage now, and we’re better prepared for the next power outage (and in our area, there will be one). I feel satisfaction and accomplishment at having done something useful, even if I can’t solve all of the problem just yet.

- Have a plan for the rest. As I said above, there are some preparedness deficiencies we can’t fix yet. But I’ve learned from sad experience that if I don’t have a plan in place for when we get back to normal-enough I’ll likely forget to do anything at all. I can take this time now to at least come up with a plan so that I know the next steps to take once we can take them.

- It’s difficult to be prepared for everything. I’ve been a homeowner for over twenty years. In this part of the world we have to be on guard against mice. Right before our state went into quarantine we discovered something entirely new: rats. Mice we could have dealt with. Nothing we had worked on rats. And even after some online research and a curbside pickup purchase it took a long time to figure out what would work.

I could probably go on, but I’m hearing too many heads hitting keyboards already, so I’l spare you. This quarantine experience has certainly given us a lot to think about, and a lot of time in which to think about it. Right now the biggest question we should all ask is, “What do I do about it?” What are we going to change as a result of our experiences? Set a goal, make a plan, and get it done.